How to Prevent Sudden Death in Sport

Written and verified by the doctor Leonardo Biolatto

News about athletes who die while exercising has often gone viral on social networks and news sites. As a result, many specialists have started to discuss different ways in which sudden death in sport can be prevented.

But is this possible? Is there really a way to detect the problem in time to prevent the fatal outcome? And, if so, shouldn’t these be the same measures that doctors take for the general population?

In this article, we’ll take a look at this topic.

Some facts about sudden death in sport

Sudden death, wherever it occurs, is when a previously healthy person’s heart stops suddenly while they’re exercising or playing a sport. This means that there’s apparently no illness that could justify that outcome.

However, when post mortems are carried out, experts usually find that there was something going on in the background.

When we consider athletes as a general group, there’s no significant difference in cases if we compare them with the rest of the population. However, among those who carry out the intense exercise, the incidences do increase, reaching more than one sudden death per 100,000 inhabitants.

Records report that most of these deaths occur in the springtime and in the afternoon. These are the usual times that competitions take place in each hemisphere of the planet.

When an athlete dies playing a sport without any apparent cause of death, up to 90% of the time there is an underlying cardiovascular cause. This is highly age-dependent, as the risk is almost non-existent among under-35s. However, in the older population, figures can be as high as 1 death per 18,000 inhabitants.

Another good article on the subject: What You Didn’t Know about Cardiac Arrhythmias

Causes of sudden death in sport

When it comes down to it, sudden death, whether in sport or outside of it, is triggered by an arrhythmia, which is ventricular fibrillation. In this condition, the lower part of the heart (the ventricles) beats unevenly, and the organ is unable to send blood to the tissues.

Atheromatous plaques were found to be the primary cause in most patients when the post mortem was carried out. These are an accumulation of clots attached to the arteries, formed by blood cells, platelets, fibrous tissue, and cholesterol.

Experts suspect that, when exercising, the atheromatous plaque breaks down and obstructs circulation abruptly. When this occurs in the coronary arteries, which are the ones that supply the heart, they cut off the supply of oxygen and nutrients. The end result here is a cell necrosis – cell death.

To a lesser extent, there are hereditary causes that can’t be prevented about sudden death in sport. However, as we’ll see below, they can often be detected in time with an electrocardiogram.

Two of the best-known forms from a genetic point of view are:

- Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. The cells of the heart degenerate and are converted from muscle to fat. In the long run, these cardiac areas lose functionality and produce repetitive arrhythmias, especially during intense effort.

- Hypertrophy. In these patients, the wall of the heart progressively increases in size. This makes it increasingly difficult for blood to leave the ventricles and be distributed throughout the body. When the heart can expand no more, sudden death occurs.

How can you prevent sudden death in sport?

Knowing the causes and ways in which this occurs, it’s worth looking into how to prevent sudden death in sport. The first step here is almost always to carry out a physical examination on all athletes using an electrocardiogram.

The truth is that, in legal terms, many countries require this examination to certify for federated or professional activities. However, there’s currently a considerable scientific discussion about its true value in this field. In the case of genetics and heredity, the test could help, but atheromatous plaques don’t give off any electrical signals.

For this reason, there’s currently talk of a more thorough medical examination that includes more elements than just the electrocardiogram. People are calling for a good physical examination with age-appropriate laboratories and the possibility of special complementary methods if any suspicions arise.

We need to remember here that atheromatous plaques are more frequent at a later age, but they aren’t so easy to detect. On the other hand, the same recommendations apply to sportsmen and women as to the general population as regards risk factors. Because of this, everyone should consider the following guidelines:

- Controlling obesity

- Regulating blood pressure and blood sugar levels

- Reducing bad cholesterol

- Following a healthy diet

- Avoiding alcohol and tobacco

Prevention at a social level

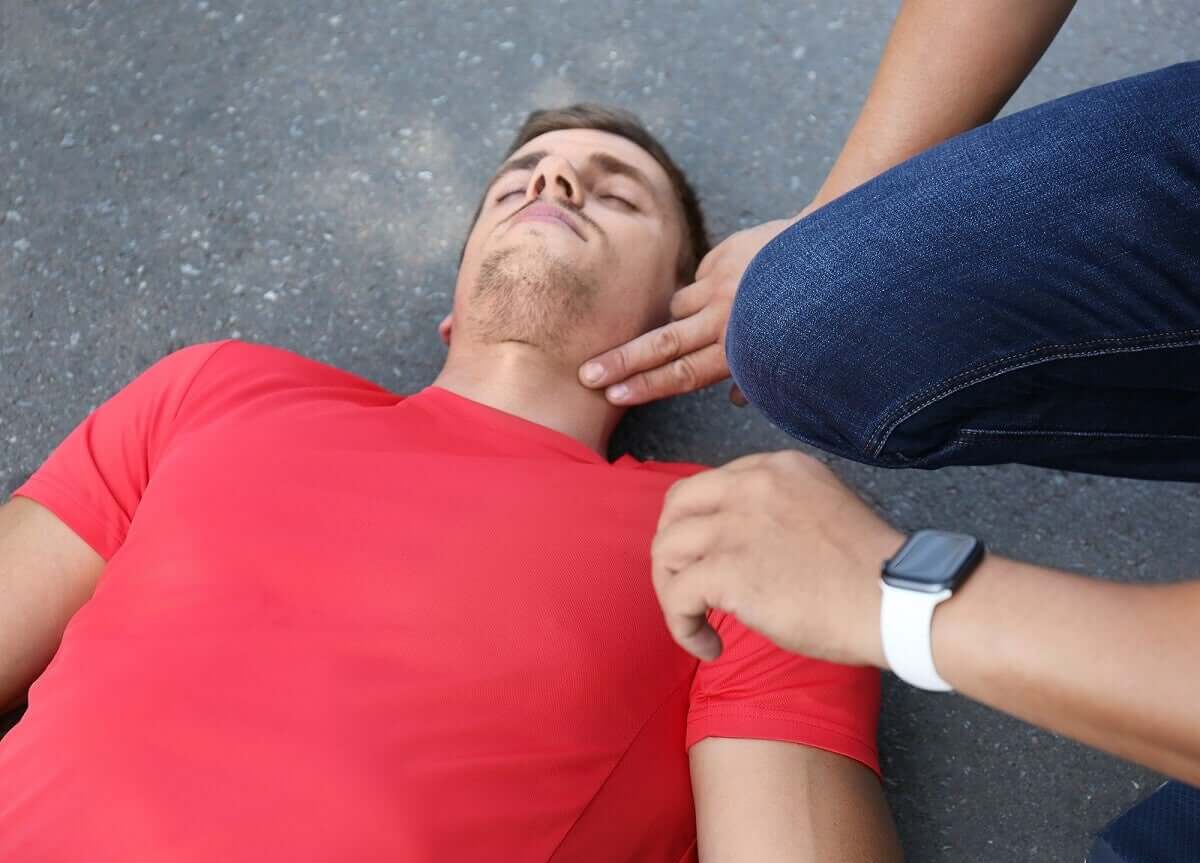

Automatic defibrillators should be installed in sports facilities and staff should be familiar with the basic steps for cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. Similarly, coaches and referees should be trained in resuscitation.

A warning system is essential. Setting up procedures to notify the emergency services is essential in sporting and other public establishments. Workers should know how to carry out these procedures with speed and precision. This should be clear in any gymnasium and stadium, with people responsible for calling, and trained in the steps they should take.

Find out more: 7 steps to interpreting an electrocardiogram

A remote possibility, but one that exists

If we look at the figures, we could say that the incidence of sudden death in sport is low. And perhaps it is low for the general population as a whole. However, the figures for people over 50 years of age who carry out intense exercise are significant.

For this reason, this age group must take extreme care. They must have regular check-ups, and consider them essential – not as a mere formality. Doctors should carry out all the complementary methods requested, and assess them in the context of the patient in question.

There’s also an overall responsibility in society, especially for sports centers and those who organize sporting events. Having defibrillators in visible areas, training in health education on the subject, and procedures to be carried out in the event of problems are all elements that can contribute to reducing the problem.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Suárez-Mier, M. Paz, and Beatriz Aguilera. “Causas de muerte súbita asociada al deporte en España.” Revista española de cardiología 55.4 (2002): 347-358.

- Iglesias, Diego Esteban. “Muerte súbita en el deporte.” La Revista del Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires 36 (2016): 91-98.

- de Luna, Antoni Bayés, et al. “Actualización de la muerte súbita cardiaca: epidemiología y estratificación del riesgo.” Revista española de medicina legal 44.1 (2018): 5-12.

- Morentin, Benito, Ma Paz Suárez-Mier, and Beatriz Aguilera. “Muerte súbita por enfermedad ateromatosa coronaria en jóvenes.” Revista Española de Cardiología 54.10 (2001): 1167-1174.

- Manonelles Marqueta, P., et al. “Estudio de la muerte súbita en deportistas españoles.” Investigación cardiovascular 9 (2006): 55-73.

- Sitges, Marta, et al. “Consenso para prevenir la muerte súbita cardíaca de los deportistas.” Apunts: Medicina de l’esport 48.177 (2013): 35-41.

- Aparicio Rodrigo, María, and Enrique Rodríguez-Salinas Pérez. “Dudas sobre la utilidad del cribado masivo con electrocardiograma en deportistas para prevenir la muerte súbita.” Pediatría Atención Primaria 18.71 (2016): 275-278.

- Serratosa-Fernández, Luis, et al. “Comentarios a los nuevos criterios internacionales para la interpretación del electrocardiograma del deportista.” Revista Española de Cardiología 70.11 (2017): 983-990.

- de Viguri, Narciso Perales Rodríguez, José Luis Pérez Vela, and Cristina Pérez Castaño. “Respuesta comunitaria a la muerte súbita: resucitación cardiopulmonar con desfibrilación temprana.” Revista Española de Cardiología Suplementos 10 (2010): 21A-31A.

- Armengol, Juan Jorge González, Antonio López Farré, and Fernando Prados Roa. “Síncope de esfuerzo y riesgo de muerte súbita en deportistas jóvenes: perspectiva clínica y genética.” Emergencias: Revista de la Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias 23.1 (2011): 47-58.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.