These Are the 4 Most Dangerous Fungi for Our Health According to the WHO

Written and verified by the doctor Leonardo Biolatto

The World Health Organization (WHO) produced a report to catalog the fungi that are most dangerous to human health. Published in October 2022, under the title List of priority fungal pathogens to guide public health research, development, and action.

After a series of meetings between specialists, it was established that four of the 19 fungi listed merit priority action. This is because they are more resistant to drugs, are more lethal, and leave serious after-effects in patients.

Thus, the fungi most dangerous to human health, at present and according to the WHO, are the following:

- Candida auris

- Candida albicans

- Aspergillus fumigatus

- Cryptococcus neoformans

Fungal infections are on the rise and are more resistant than ever to treatment, making them a global public health problem. -Hanan Balkhy, WHO Assistant Director-General

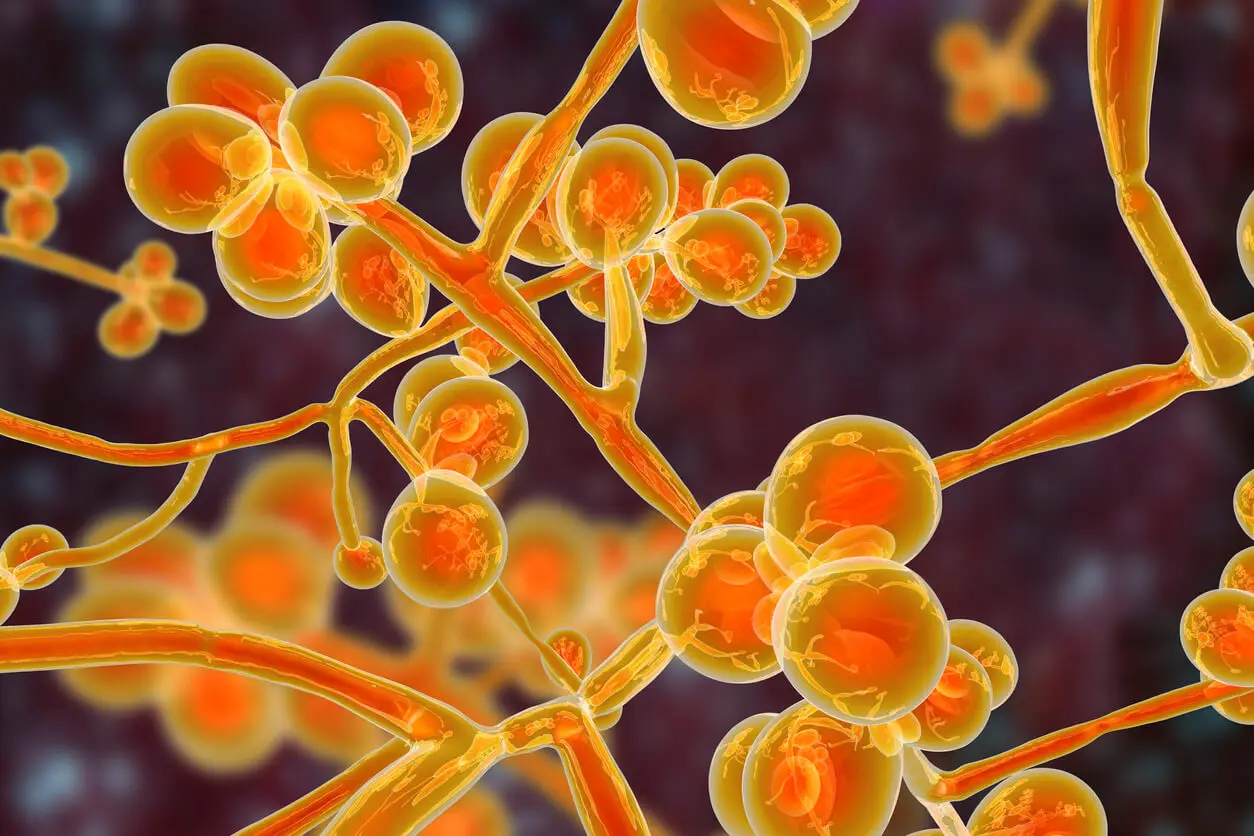

1. The most dangerous fungi: Candida auris

This fungus is one of the most dangerous to human health, partly because it has only recently been discovered. The first specific record dates back to 2009. Then, in 2011, a case of generalized infection in a patient became known. Although this was an isolated case, the following year the first in-hospital outbreak of C. auris was reported.

Currently, more than 40 countries have already reported cases of this pathogen. The problem is that its emerging and novel nature makes it difficult to identify with classical diagnostic methods.

So far, most of the infected patients have had to be treated with a combination of antifungals, as the strains have tended to be drug-resistant. Statistics indicate that up to 30% of patients die within the first month of infection.

Since its isolation in the ear canal of a person in Japan, hospital outbreaks of C. auris have increased. Some healthcare facilities found its presence on the walls of inpatient wards. In fact, the deaths of newborns in Venezuela, in 2013, were the alarm bell that shocked the medical world.

A 2019 scientific study affirmed that disinfectants commonly used in hospitals and clinics do not work against this fungus. Therefore, different antisepsis and disinfection measures are required to prevent outbreaks.

What disease does it cause?

According to a publication by Han Du and collaborators, this is one of the most dangerous fungi for human health because it can be found in many different tissues and secretions. It has already been isolated in blood, urine, skin, and rectal mucosa.

It could reproduce inside the digestive tract and in anaerobic environments, i.e. with no or low concentrations of oxygen. It also has the ability to colonize the oral mucosa and, from there, spread into the blood.

It is considered an opportunistic pathogen.

This means that it takes advantage of weakened immune systems. Therefore, patients in intensive care units are at great risk. It’s possible for a widespread infection to develop in them, leading to shock.

We think you may also enjoy reading this article: Red Spots on the Skin: 25 Possible Causes and Treatments

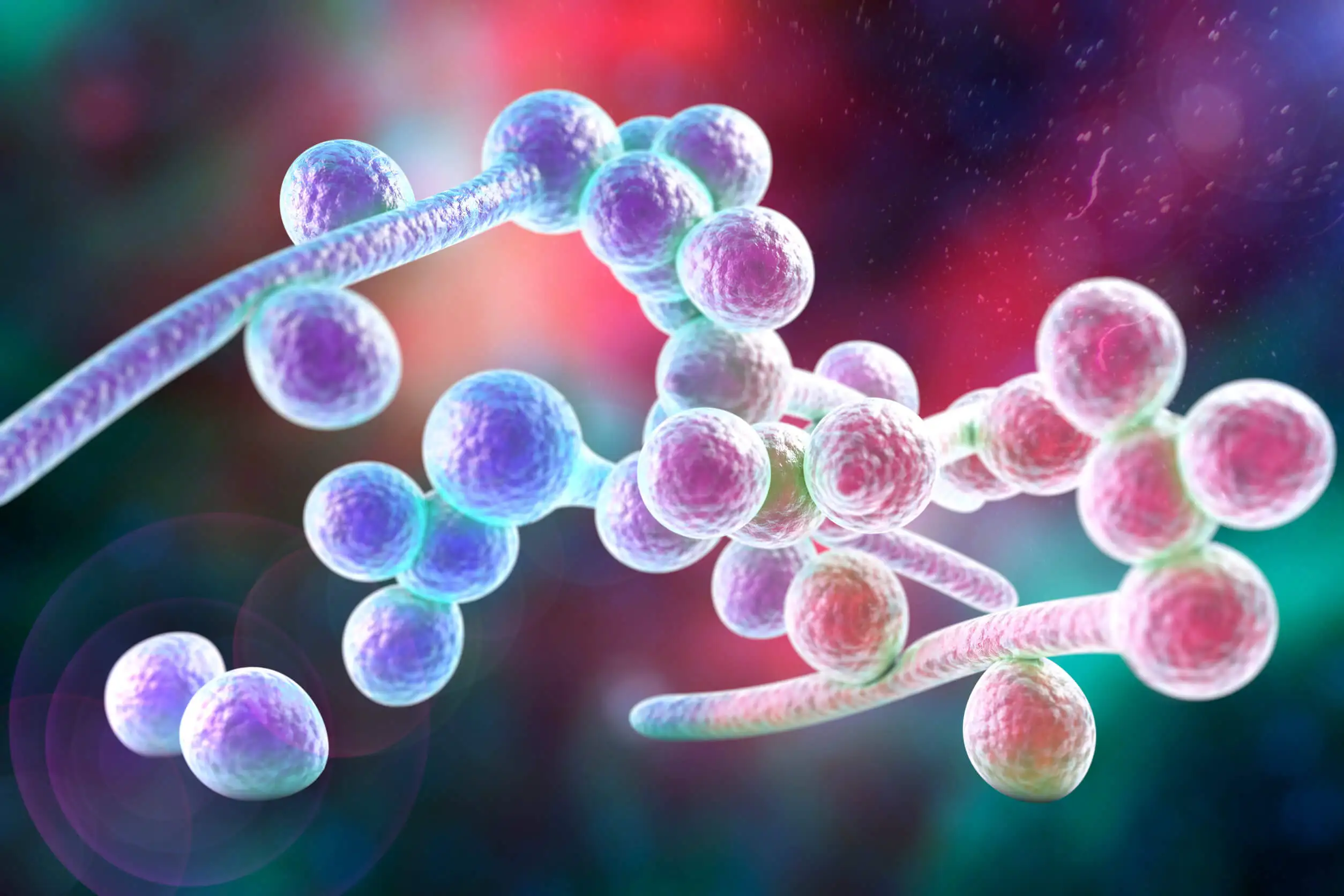

2. Candida albicans

Unlike the previous fungus, C. albicans is quite well known. While easier to diagnose in its usual presentations in the mouth, skin, and vagina, the same is not true for the septicemias it can trigger in susceptible patients.

When it acts as an opportunist, taking advantage of a patient’s diminished defenses, it wreaks havoc. In its invasive form, it reaches the blood and causes fever, kidney failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Special care should be taken with people receiving chemotherapy treatment for cancer. They are particularly susceptible to C. albicans colonization. Long stays in hospital sites and the presence of a catheter to administer intravenous medication facilitate the arrival of the fungus into the bloodstream.

Three are the most classic and dangerous invasive clinical modalities of this fungus:

- Candidemia: This fungus circulates in the blood and reproduces in the blood tissue. This leads to sepsis with a fever that leads to organ failure as a whole. One of the most affected is the renal system. In addition, there’s usually a reaction to the simultaneous formation of small clots in different parts of the body.

- Esophageal: Esophageal candidiasis is the leading cause of infectious inflammation of the esophagus. In health centers where upper gastrointestinal endoscopies are performed, it’s a particular concern, since the instrument for the study can be a vehicle for the fungus, helping it to be deposited inside the patient’s gastrointestinal tract.

- Retinal: Candida endophthalmitis causes retinal problems. Although this is not an acute clinical presentation, its evolution derives in blindness if there is no timely treatment due to the fact that the inner region of the eyeball is filled with scars that hinder vision.

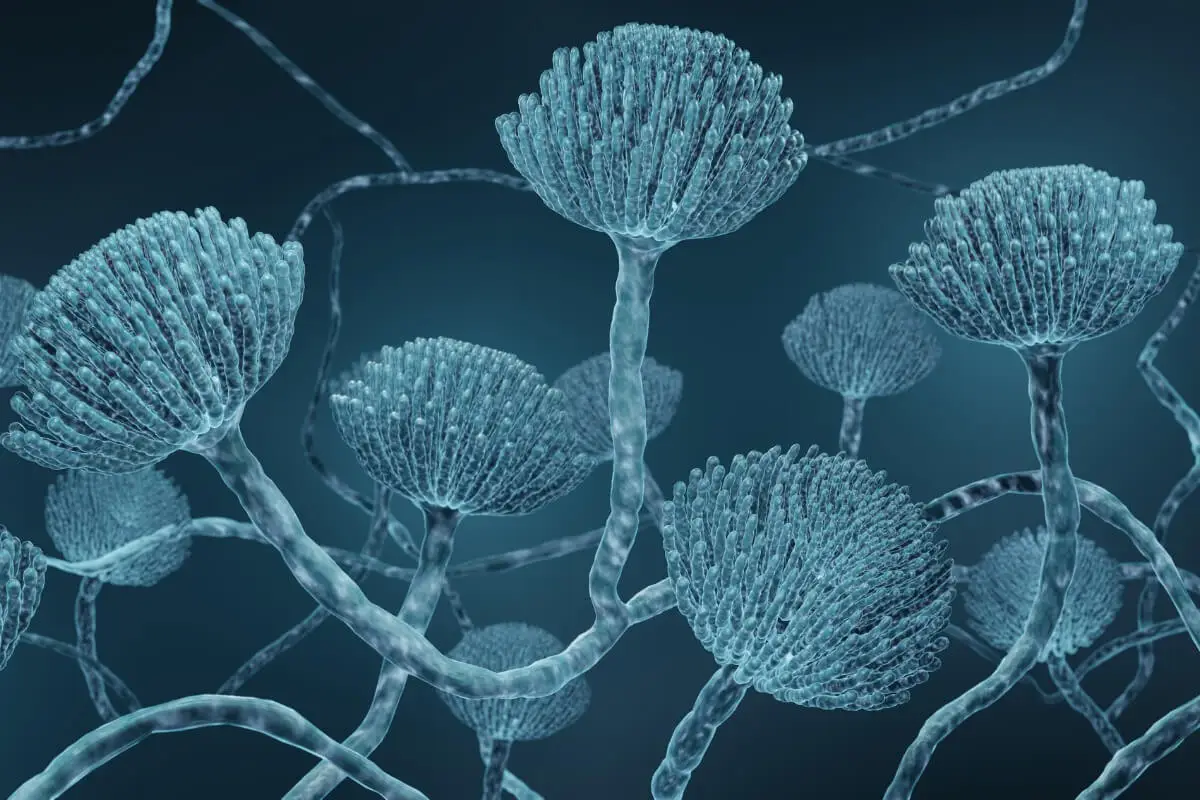

3. Aspergillus fumigatus

A 1999 review alerted about A. fumigatus as one of the most dangerous fungi for human health. Able to survive in soil and in hostile environments, it has the potential to circumvent human defenses with relative ease when immunity is compromised.

Although opportunistic, its airborne transmission is often of concern. It’s therefore one of the most common pathogens among patients with respiratory conditions in the context of immunosuppressive disease.

The pulmonary form is not always the same and, although it is generically referred to as aspergillosis, a distinction must be made between allergic, chronic, and aspergilloma presentations. In turn, an allergy has two other subforms. One is bronchopulmonary or ABPA, which consists of symptoms very similar to asthma. The other is A. fumigatus sinusitis, which presents with mucus, nasal congestion, and reduced ability to smell.

An aspergilloma is a tumor formed by an agglomeration of fungi. It occupies a space in the lung and acts as a nodule, capable of triggering cough and dyspnea or shortness of breath.

The chronic form is not uncommon in people with uncompromised immune systems. The fungus slowly colonizes the bronchial mucosa and generates long-term reactions. As far as we know, up to one-third of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are colonized by the fungus.

Like this article? You may also like to read: What’s the Difference Between Infectious and Contagious?

How is it treated?

The approach to aspergillosis depends on its presentation. Allergic forms usually respond well to itraconazole, sometimes combined with a corticosteroid to manage the symptoms of the reaction generated in the respiratory tract.

If the pathogen has invaded organs and blood, then more potent drug combinations are required. Voriconazole, amphotericin, and capsofungin are some of the drugs of choice.

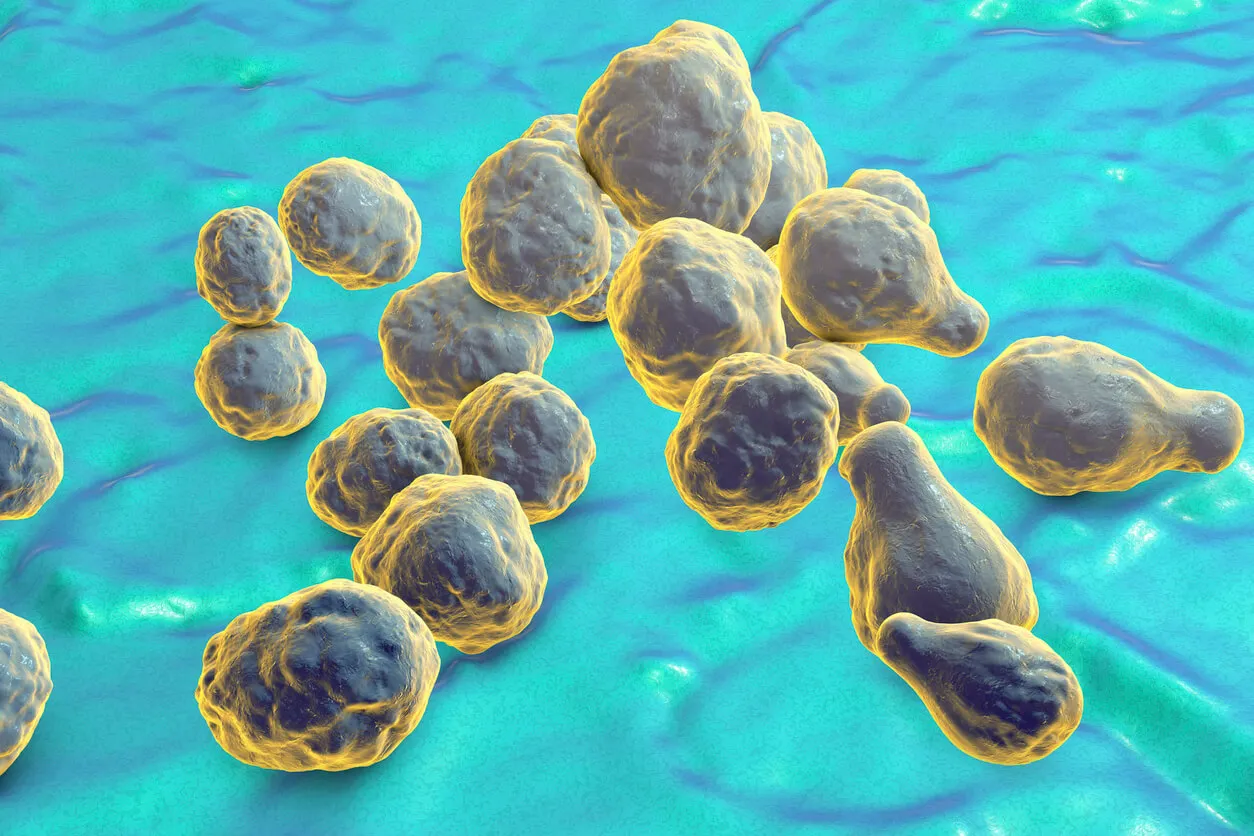

4. The most dangerous fungi: Cryptococcus neoformans

The disease that we know as cryptococcosis can be caused by this fungus or by C. gattii. However, the latter seems to be limited to some geographical areas of the world, while C. neoformans has a worldwide presence.

Like A. fumigatus, its presence in the soil makes it accessible for inhalation. It has been localized in some tree species and is shed in bird feces. Like other opportunistic pathogens, it preys on weakened immune systems in HIV/AIDS, cancer, and transplant patients.

According to statistics, 223,000 people are diagnosed with meningitis caused by this fungus each year. It’s thus the leading cause of mortality among immunocompromised patients, with more than 180,000 dying from the infection annually.

Although it’s susceptible to three different groups of antifungal drugs, its ability to resist is increasingly being recognized. Researchers believe that one of the defense mechanisms it possesses is hybridization, i.e. genetic mixing with other strains. Excessive use of pesticides in agriculture is also thought to be contributing to the process.

The special case of HIV patients

Meningeal cryptococcosis in HIV patients is a serious public health problem. It’s one of the most lethal complications for these people and early detection can be life-saving.

However, there’s another risk factor that has to do with the underlying disease itself. Those who are not on antiretroviral treatment (ART) or have just started treatment are more likely to have a fatal outcome if they contract the fungus. Rapid and equitable access to ART is therefore essential.

The fungi most hazardous to health must be researched

According to the WHO, the list of fungi most hazardous to human health has been published to encourage research in this field. New developments should solve the problem of resistance to antifungals.

In the meantime, the protection of immunocompromised and hospitalized patients is a priority. Caring for at-risk groups reduces the spread of these difficult-to-diagnose pathogens.

In addition to the four fungi mentioned above, the other 15 that make up the WHO list are as follows:

- Second priority group: Nakaseomyces glabrata, Histoplasma spp. Eumycetoma, Mucorales, Fusarium spp. Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis

- Medium priority group: Scedosporium spp. Lomentospora prolificans, Coccidioides spp. Pichia kudriavzeveii, Cryptococcus gattii, Talaromyces marneffei, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Paracoccidioides spp

We need more data and information on fungal infections and antifungal resistance to guide and improve the response to these priority fungal pathogens. -Haileyesus Getahun, WHO Director for Global Antimicrobial Resistance Coordination

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Alastruey-Izquierdo, Ana, World Health Organization, and World Health Organization. “WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action.” (2022).

- Bouchentouf, Rachid. “Aspergiloma pulmonar bilateral.” Revista de la Sociedad Peruana de Medicina Interna 34.2 (2021): 87-87.

- Collado-Chagoya, Rodrigo, et al. “Aspergilosis broncopulmonar alérgica.” Medicina Interna de México 37.1 (2021): 144-151.

- Du, Han, et al. “Candida auris: Epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence.” PLoS pathogens 16.10 (2020): e1008921.

- Fúnez-Madrid, Víctor H., et al. “Candidiasis esofágica: Análisis descriptivo en un centro de referencia endoscópica.” Endoscopia 32 (2020): 415-415.

- Geddes-McAlister, J. and Shapiro, R.S. (2018) New pathogens, new tricks: emerging, drug-resistant fungal pathogens and future prospects for antifungal therapeutics. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1435(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13739

- Latgé, Jean-Paul. “Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis.” Clinical microbiology reviews 12.2 (1999): 310-350.

- Lizarazo, Jairo, and Elizabeth Castañeda. “Consideraciones sobre la criptococosis en los pacientes con sida.” Infectio 16.3S (2012).

- May, R.C., Stone, N.R.H., Wiesner, D.L., Bicanic, T. and Nielsen, K. (2016) Cryptococcus: from environmental saprophyte to global pathogen. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 14(2), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2015.6

- Méndez-Tovar, Luis Javier, et al. “Candidiasis esofágica en pacientes de un hospital de especialidades.” Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social 57.2 (2019): 74-81.

- Mourad, A. and Perfect, J.R. (2018) Present and future therapy of Cryptococcus infections. Journal of Fungi, 4(3), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof4030079

- Pashley, Catherine H., et al. “Routine processing procedures for isolating filamentous fungi from respiratory sputum samples may underestimate fungal prevalence.” Medical mycology 50.4 (2012): 433-438.

- Perera, Sandra Gómez, et al. “Endoftalmitis endógena por cándida álbicans: a propósito de un caso.” Archivos de la Sociedad Canaria de Oftalmología 32 (2021): 7-12.

- Rajasingham, R., Smith, R.M., Park, B.J., Jarvis, J.N., Govender, N.P., Chiller, T.M., et al. (2017) Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 17(8), 873–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8

- Rhodes, Johanna, and Matthew C. Fisher. “Global epidemiology of emerging Candida auris.” Current opinion in microbiology 52 (2019): 84-89.

- Satoh, Kazuo, et al. “Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital.” Microbiology and immunology 53.1 (2009): 41-44.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.