A New Study Identifies Mouth Bacteria that May Cause Colon Cancer

Written and verified by the doctor Leonardo Biolatto

The role of bacteria in the human body can be protective or aggressive, even to the point of being linked to colon cancer. More and more studies are certifying the leading role of microbiota in our health.

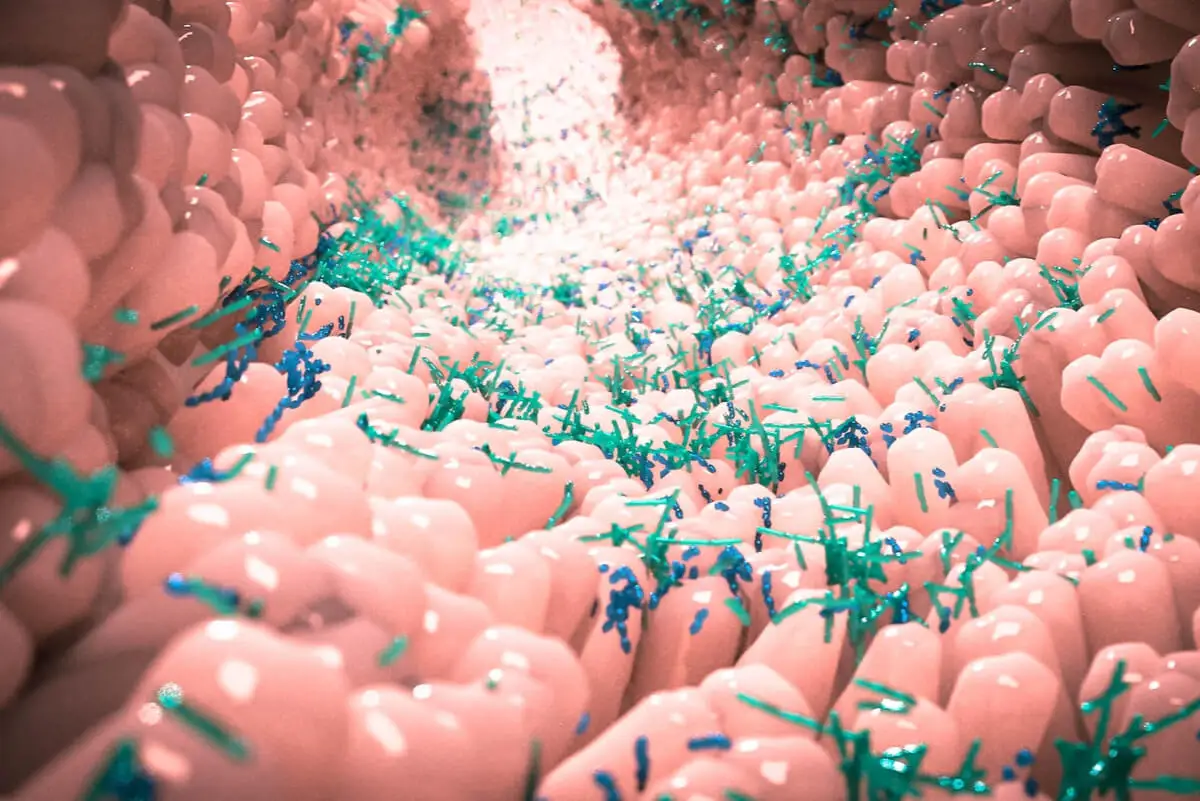

The microbiota is the group of microorganisms that coexist with the human being, sometimes in balance, sometimes not so much. Our relationship with the environment generates a progressive colonization of the skin and mucous membranes.

Thus, researchers have managed to find microorganisms that are typical of different organs. In other words, finding them there doesn’t mean that you’re sick or will develop cancer. However, there are other types of bacteria that may appear in locations they should not.

A new study has corroborated that a bacterium develops at the site of colon cancer but belongs to the mouth. Could it be a causal agent of the disease?

We think you may be interested in reading this, too: New Cancer Treatment? Photoimmunotherapy Successfully Eliminates Malignant Cells

The Spanish study

Members of the Institute of Biomedical Research of A Coruña published their results on the Research Square platform. There, they report that a bacterium from the mouth also inhabits the microenvironment surrounding colon cancer in some patients.

After analyzing many different samples, they were able to identify Parvimonas micra in intestinal tumors. This microorganism had previously been detected in saliva and specifically in the gums of people with periodontitis.

When analyses were performed to compare the genetic information of bacteria from the mouth with those from colon cancer, a 99.2 % similarity was found. This means that bacterial colonies from the mouth were able to migrate to the large intestine, settle there, and proliferate.

The definitive data linking P. micra to the oncological process is that healthy people don’t have this bacteria present in their colon. Moreover, the microorganism is metabolically more active when it is found among malignant cells than if it is located in healthy tissues.

What we have been doing for years is analyzing the microbiome of colorectal cancer patients. It has been known for some time that the microbiome interacts with our cells and under certain circumstances can lead the the development of diseases. -Marga Poza, INIBIC researcher

What may cause colon cancer: An old and new acquaintance

Parvimonas micra is not an unknown bacterium in the medical world. This Gram-positive anaerobic coccus has been listed as one of the agents present in periodontitis for years. Many of its actions have been recognized in dentistry.

Less frequently, the bacterium has been associated with septic arthritis, brain abscesses, and even endocarditis. In fact, it was only in 2015 that its presence in infected heart tissue was documented for the first time.

A characteristic of this bacterium is that it can join with different bacteria to form clusters, films, biofilms, and collaborative aggregations. It does so in the case of periodontitis and may do so in colon cancer as well.

Researchers suspect that its journey from the mouth to the gut doesn’t happen alone. Instead, it takes advantage of the binding ability to move in groups to distant areas of the human body and create a favorable microclimate and form new colonies.

P. micra colonies produce different substances by their metabolism. The mere fact of developing leads them to secrete molecules that could be harmful or toxic to the host organism.

Ultimately, the suspicion is that certain substances in the microorganisms trigger the malignant transformation of human cells.

Like this article? You may also like to read: Testicular Cancer: The Disease that Borussia Dortmund’s Sebastien Haller Has

Not just bacteria can cause colon cancer

It would be very simplistic to say that a bacterium is the origin of colon cancer. Science knows that there are multiple factors capable of triggering a neoplasm.

The microbiota is just one more element in a complex web of circumstances, characteristics, and situations that lead to a tumor. Diet, stress, a sedentary lifestyle, and genetic inheritance are also all risk factors for colorectal cancer.

One hypothesis is that bacteria from the mouth manage to reproduce in the intestine when they encounter reduced defenses. This could be due to stress or poor diet.

Once a colony of P. micra is established, it becomes difficult to eradicate. In combination with other microorganisms, it can manufacture a real defensive fortress to prevent the human immune system from detecting and eliminating it.

Bacteria do not directly cause cancer, but they can worsen the prognosis

There are other bacteria that have been found in tissues with colorectal cancer. One of them is Fusobacterium nucleatum.

The latter is linked to a worse prognosis. This means that patients who carry it in their malignant tissue tend to live shorter lives and respond worse to treatments. Similarly, it could be involved in metastasis.

So, a bacterium may not only promote colon cancer, but be a negative prognostic factor. Although more data are needed to clarify the situation, it does not seem unlikely that bacterial clusters contribute to a more aggressive and more difficult-to-treat disease.

What is the significance of this discovery?

Early diagnosis of neoplasms is a public health obsession. Having precise, early, and specific methods to know if a person has cancer would increase the effectiveness of treatments.

For Marga Poza, bacteria are possible biomarkers of colorectal cancer:

“The person who has this bacterium in the intestine could be suffering from colon cancer, in its early stages, or it may have even already advanced.” -Marga Poza

The development of a laboratory or outpatient test to verify the presence of P. micra in the intestine could open the door to initiating a thorough screening in that patient. Hopefully, a tumor can therefore be found in its early stage and can be successfully removed. Thus, there would be few side effects, and the person would go on with life as usual.

We all live with bacteria, most of which are harmless, but some of which can indeed be a sign of an imbalance in the body. They are there and can tell us important things about our health. That’s why scientists are investigating them.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Baghban, Adam, and Shaili Gupta. “Parvimonas micra: a rare cause of native joint septic arthritis.” Anaerobe 39 (2016): 26-27.

- Bullman, Susan, et al. “Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer.” Science 358.6369 (2017): 1443-1448.

- Conde-Pérez, Kelly, et al. “Evidence for translocation of oral Parvimonas micra from the subgingival sulcus of the human oral cavity to the colorectal adenocarcinoma.” (2022).

- Gomez, Carlos A., et al. “First case of infectious endocarditis caused by Parvimonas micra.” Anaerobe 36 (2015): 53-55.

- Ho, Dawn, et al. “An unusual presentation of Parvimonas micra infective endocarditis.” Cureus 10.10 (2018).

- Horiuchi, Akira, et al. “Synergistic biofilm formation by Parvimonas micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum.” Anaerobe 62 (2020): 102100.

- Kim, Eun Young, et al. “Concomitant liver and brain abscesses caused by Parvimonas micra.” The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology 73.4 (2019): 230-234.

- Mima, Kosuke, et al. “Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis.” Gut 65.12 (2016): 1973-1980.

- Rams, Thomas E., Jacqueline D. Sautter, and Arie J. van Winkelhoff. “Antibiotic resistance of human periodontal pathogen Parvimonas micra over 10 years.” Antibiotics 9.10 (2020): 709.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.