The Amazing Process of Peristalsis

Written and verified by the doctor Leonardo Biolatto

Peristalsis are muscle contractions that occur in the tube-like organs of the human body. This includes the gastrointestinal tract and also the urinary tract, where tube-shaped structures transport substances.

Peristalsis contractions are organized and rhythmic. They occur at a frequency that’s considered normal and through the smooth muscle present in the walls of tube-like organs.

The smooth muscle is autonomous. In other words, it’s involuntary. You can’t give this muscle conscious orders to contract. Thus, it depends solely on brain orders you have no control over.

When the brain becomes aware of the presence of food in the digestive tract, it sends the order to the smooth muscle of the bodies involved to perform certain movements. These movements generate the transport of food from the mouth to the anus.

The same mechanism also applies to the urinary system. When the brain detects the presence of urine produced by the kidneys, it sends information so the ureters transport it to the bladder by peristalsis.

Thus, we could say that peristalsis has three main functions:

- Propelling food into the digestive tract.

- Circulating bile in the liver, which is part of the digestive system.

- Transferring urine to the urinary tract.

The steps of peristalsis

Peristalsis moves the bolus through the digestive system.

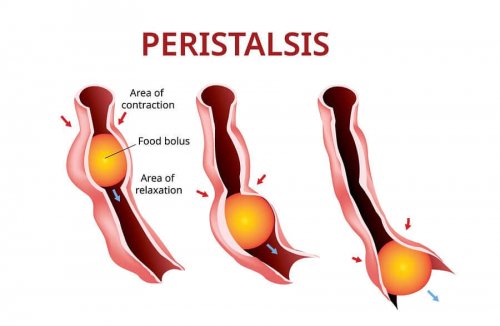

In addition, it occurs rhythmically and in an organized manner. Once food enters the mouth and is crushed, it then reaches the esophagus. There, peristalsis is responsible for moving the bolus (see diagram) that’s been created to the stomach. These same movements prevent the bolus from going back up.

When the stomach secretes gastric acid and does the appropriate actions on the bolus, the next stage of the journey is the small intestine. Then, peristalsis transfers the substances to the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. There, bile acids from the gallbladder are added.

In the small intestine, nutrient absorption depends on good peristalsis, as well-executed movements allow the displacement of small substances into the intestinal walls.

Finally, the digested food will be dehydrated in the large intestine. Here, the coordinated movements play a key role in fecal expulsion. Both the rectum and anus depend on these movements to do the last step.

Keep reading: Three Ideal Recipes for People with Digestive Problems

Causes of decreased peristalsis

Due to various reasons we’ll explain below, a person’s peristaltic movements may be slower than usual. This can lead to constipation in the digestive tract. And constipation can lead to health problems.

Among the most common causes of decreased peristalsis are:

- Extreme ages. Both the elderly and young children are more likely to suffer from constipation because their ages produce deficits in the smooth muscle.

- Diabetes. This disease affects neurological transmissions in many bodily regions, including the digestive system.

- Parkinson’s disease. Patients who suffer from this condition may also suffer from more frequent constipation.

- Autoimmune diseases. For example, patients with scleroderma or polymyositis have decreased peristalsis.

- Drugs. Some drugs have side effects such as constipation and decreased peristaltic activity. Thus, it’s important to know that possibility before consuming them and consulting with your prescribing physician so that you don’t get afraid if it happens to you.

Childhood is characterized by changes in the peristaltic rhythm.

This article may interest you: Childhood Constipation: What it Is and What to Do

Causes of increased peristalsis

Just as you can suffer from decreased peristalsis, the movements can also increase more than necessary, causing the final effect of diarrhea. These are the most common causes:

- Bacterial infections. The most common bacteria that cause diarrhea are Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and also Shigella. The patient may have contracted them from ingesting poisoned food or water.

- Viral infections. In children, increased peristalsis occurs due to common viruses. Medical monitoring is essential in these cases in order to avoid dehydration.

- Drugs. Just as certain drugs have adverse effects, including constipation, others can cause diarrhea.

- Chronic diseases. Some highly prevalent diseases in the general population have a symptom associated with increased peristalsis. For example, we can mention thyroid gland dysfunctions.

- Psychological origin. The intestine responds to stressful situations. This may seem logical now, since you now know that the movements depend on the nervous system that stimulates the smooth muscle.

- Prior digestive surgery. Those who have undergone gastric or intestinal surgery for various reasons may suffer from future peristaltic rhythm changes, either by the destruction of the intervening nerve fibers or by the shortening of the digestive tract.

Conclusion

In summary, peristalsis is a normal and vital bodily function. Without it, you couldn’t live normally. It’s responsible for transporting food through the digestive tract and urine in the urinary system.

However, its normal function may be impaired. Thus, you must consult your doctor if you notice that you’re having more or fewer bowel movements. Your doctor will know if it’s a momentary change or if it’s something that requires specific treatment.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Loeb, Gerald E., and Frances JR Richmond. “Method and apparatus to treat disorders of gastrointestinal peristalsis.” U.S. Patent No. 6,895,279. 17 May 2005.

- Quevedo Guanche, Lázaro. “Oclusión intestinal: Clasificación, diagnóstico y tratamiento.” Revista Cubana de Cirugía 46.3 (2007): 0-0.

- Angosto, María Cascales, and Antonio L. Doadrio Villarejo. “Fisiología del aparato digestivo.” Monografías de la Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia (2014).

- Philpott HL, Nandurkar S, Lubel J, Gibson PR. Drug-induced gastrointestinal disorders. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5(1):49–57. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2013-100316

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.