How to Maintain Bone Density after Menopause

All women start to undergo changes in their bodies during menopause due to the hormonal changes it causes. Due to the decreased production of estrogen, the risk increases for developing various chronic illnesses, including different types of cancer, diabetes and issues with bone density, like osteoporosis.

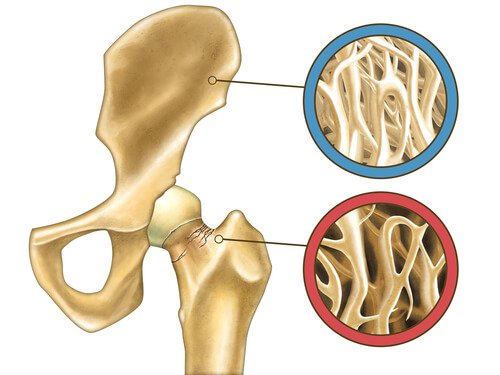

This last one demands special attention as the loss of hormones causes a decrease in bone density, which increases your risk for developing the disease.

In recent years, it’s been determined that during the last 5 years of menopause, a woman can experience a .5% reduction in bone density each year.

For this reason, it’s recommended that when you reach this stage, you develop healthy habits that will help conserve it.

What’s the Link Between Bone Loss and Menopause?

From the first few years of life until approximately age 30, the body has the ability to maintain a balance between bone loss and production. Then between age 30 and 35, the loss starts to occur faster than the body can replace it, which makes it really important to start boosting its production.

With the ending of menstruation upon reaching menopause (at approximately age 50), the loss of bone density accelerates considerably. Due to the reduced levels of estrogen, the bones become weak and more susceptible to breakage.

See also: Prunes to Prevent Bone Mass Loss

Who’s Most at Risk for Losing Bone Density?

Women with a family history of osteopenia or osteoporosis have a greater risk of developing this problem. However, the following factors can also influence the development of this disease:

- Being too thin or petite.

- Obesity.

- Taking corticosteroid medication.

- Hyperthyroidism.

- Eating a diet that’s low in calcium and vitamin D.

- Drinking alcohol in excess or smoking.

- A sedentary lifestyle.

Is it Possible to Minimize Bone Loss?

Once lost, bone density is difficult to recover. However, there are steps you can take to reduce the risks like adopting a healthier lifestyle to preserve it so that your bone health isn’t compromised.

Adopting the following habits is recommended before and during menopause to prevent the accelerated reduction in bone mass and bone disease.

Consume More Calcium

Calcium is one of the most important minerals for bone health as its a key component in bone composition.

Between the ages of 30 and 35, taking 1200 mg of calcium every day is recommended. Then, when approaching menopause, the dosage should be increased to 1500 mg of calcium per day.

The best sources of calcium include:

- Milk and dairy products

- Green, leafy vegetables like kale, broccoli and cabbage

- Cold water fish

- Soy and rice milk

- Orange juice

- Calcium supplements

Avoid Consuming too Much Sodium

The kidneys filter out calcium with sodium, so consuming a lot of sodium can be harmful to your bones.

Salty foods, table salt and any source of sodium increases the excretion of calcium in the urine.

Vitamin D

The body requires a good dose of vitamin D to absorb calcium and integrate it into the bones.

Adults require 800 IU (International Units) of vitamin D each day. After age 50, this amount increases to 1,000 IU per day.

Sources of vitamin D include:

- Cereals enriched with vitamin D

- Milk

- Egg yolks

- Saltwater fish

- Liver

Sunlight allows the skin to produce vitamin D, but exposure must be moderate as it increases the risk of skin cancer and other changes in the skin. Thus, make sure to protect your skin but also enjoy plenty of time outside.

We recommend reading: How Does Vitamin D Deficiency Affect Your Body?

Exercise

One of the best ways to keep your bones healthy and strong is through exercise.

Getting the body moving by jogging, walking, swimming, weight lifting or with other exercises maintains bone density and helps prevent osteoporosis.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Sahni, S., Mangano, K. M., McLean, R. R., Hannan, M. T., & Kiel, D. P. (2015). Dietary approaches for bone health: lessons from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Current osteoporosis reports, 13(4), 245-255. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11914-015-0272-1

- Lindsay, R. (1996). The menopause and osteoporosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 87(2), 16S-19S. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0029784495004300

- Munch, S., & Shapiro, S. (2006). The silent thief: osteoporosis and women’s health care across the life span. Health & social work, 31(1), 44-53. https://academic.oup.com/hsw/article-abstract/31/1/44/628204

- Finkelstein, J. S., Brockwell, S. E., Mehta, V., Greendale, G. A., Sowers, M. R., Ettinger, B., … & Neer, R. M. (2008). Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(3), 861-868. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2266953/

- Quesada Gómez, J. M., & Sosa Henríquez, M. (2011). Nutrición y osteoporosis. Calcio y vitamina D. Revista de Osteoporosis y metabolismo mineral, 3(4), 165-182. https://medes.com/publication/71596

- Ferragut, C., Torres-Luque, G., Alacid-Cárceles, F., & Sainz de Baranda, P. (2009). Masa ósea y ejercicio físico. Arch Med Deporte, 129, 46-60. http://femede.es/documentos/Revision_Masa_Osea_46_129.pdf

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.