Nephritic Colic: Symptoms, Causes and Treatment

Written and verified by the doctor Leonardo Biolatto

Nephritic colic is one of the most intense pains a person can suffer from. Those who have suffered from it understand exactly what we’re talking about. It’s located in the lumbar zone, near kidneys or a little below, where the urinary tract is located.

The characteristic of any pain that’s called ‘colic’ is in its spasmodic behavior. The pain appears and disappears, rhythmically, causing intense peaks of pain with small periods of relaxation in between.

In the case of nephritic colic, the pain originates in the urinary system due to an obstruction in the path that the urine must travel to reach the bladder. When an obstruction appears in the system, the urinary tract tries to overcome it by contracting its ducts. This contraction is known as a colic.

The pain of nephritic colic is located in the lumbar region and radiates to the inguinal area of the person who suffers it, forming a semi-belt. It’ll be on the left or right side, depending on where the obstruction is located.

Causes of nephritic colic

The cause of the pain is a blockage of the urinary tract. This obstruction doesn’t allow the urine formed in the kidney to circulate to the bladder. Although kidney stones are the most common cause of obstruction, which is why we have a whole section in them, there are also other causes.

Among the malignant causes of obstruction are cancerous tumors of the renal system, either kidney, ureters, or those of the bladder that grow upwards. It can also be a malignant tumor of an adjacent organ that squeezes the urinary tract, as is the case with intestinal cancers, for example.

Among the benign causes we have the aneurysm of the aorta: a dilation of the aortic artery in its passage through the abdomen which can put pressure on the ureter by squeezing it. It also causes obstruction by retroperitoneal fibrosis, a formation of fibrous tissue in the back of the abdomen.

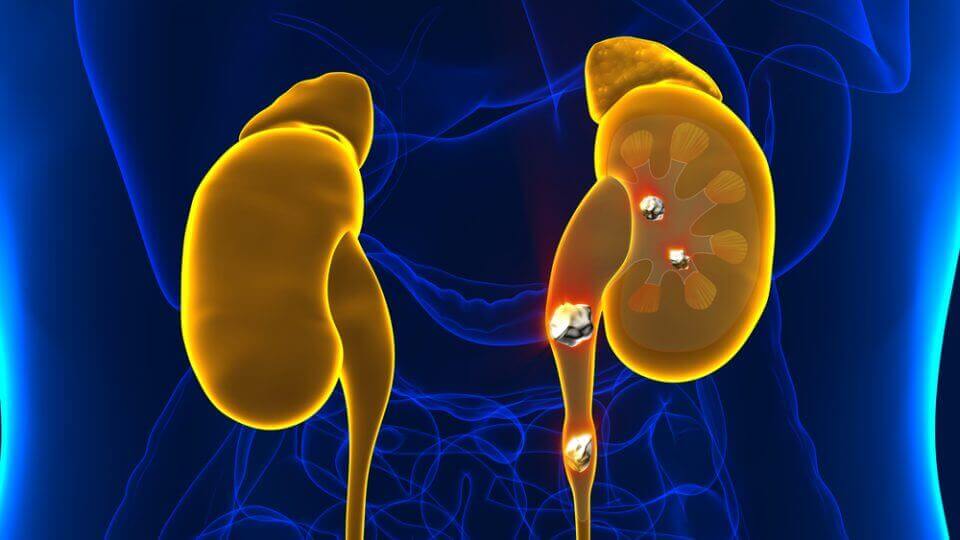

Kidney stones

As we’ve said, the most frequent cause of nephritic colic is kidney stones. These are stones of different sizes that are located in the kidneys or in the ureter. When they try to leave the body, they cause the obstruction and the consequent pain.

The stones are calcium in almost 80% of the cases. For this reason, certain situations in the human body are linked to the increased probability of suffering them. Thus, when there is hypoparathyroidism, sedentarism, prostration for a long time, or excessive consumption of external calcium -in tablets- its formation is more likely.

People who suffer from repeated urinary infections also have a greater chance of forming kidney stones. It’s more frequent among women than among men. Patients who carry a urinary catheter are more exposed to infections and, therefore, more likely to develop stones.

Less than 10% of kidney stones are uric acid. It’s common in patients with gout disorder. Sometimes, diets that are excessively rich in protein – gym and bodybuilding diets – which increase the uric acid in the blood, culminate in causing stones.

Lastly, less than 1% of stones are linked to a genetic disease called cystinuria. It’s rare and is transmitted from parents to children due to genetics.

To keep reading: Discover The Right Diet for Kidney Stones

Symptoms of nephritic colic

The most noticeable symptom of nephritic colic is the pain we’ve already described. It appears suddenly and is extremely intense. It begins in the lower back and radiates forward to the groin like a half-belt. This pain is usually accompanied by:

- Fever. This isn’t always present. It can be caused by the pain itself or by a concomitant urinary tract infection.

- Dysuria: This is the difficulty in expelling urine, which is related to the obstruction.

- Pollakiuria: This is the increased frequency of urination. The patient urinates more often, but small amounts each time.

- Hematuria: In some cases, the stones can damage the urethra and cause some blood in the urine.

Diagnosis and treatment

Doctors are usually very quick to diagnose nephritic colic once the symptoms are established. The pain is very characteristic and not many other illnesses have the same symptoms. However, doctors have to perform urinalysis and x-rays to complement the diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis is achieved with a renal and bladder ultrasound, where, in the vast majority of cases, the presence of the obstruction is identified and, in the case of the stones, their size. Only very unclear clinical pictures require a tomography.

Once diagnosed, treatment is based on analgesia. The priority is to calm the patient’s pain. For this purpose, doctors prescribe anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs. They can be administered orally or intramuscularly. Doctors opt for the intravenous route when the pain is too intense or the patient is vomiting.

For more information: Gallbladder Diet Do’s and Don’ts

Treatment after the pain

Once the pain clears up, the next step is to program the resolution of the obstruction. If it’s a pathology that requires surgery, the doctors will program it ahead of time. However, if it’s a kidney stone, there are various therapeutic options:

- Hydration: When the patient has small stones, it’s better to wait for spontaneous expulsion. Patients help the process by drinking plenty of liquid.

- Shock wave lithotripsy: This is a procedure that uses waves from outside the body to break up the stones so that they can be urinated out like sand.

- Ureteroscopy: This is the surgical removal of larger stones. The doctors perform an endoscopic insertion of a device through the urinary tract until they’re able to remove the stones.

All cited sources were thoroughly reviewed by our team to ensure their quality, reliability, currency, and validity. The bibliography of this article was considered reliable and of academic or scientific accuracy.

- Navarrete, Jose Ignacio Massa, et al. “Manejo del cólico renal en Urgencias.” Seram (2018).

- Nicolau, Carlos, Rafael Salvador, and J. M. Artigas. “Manejo diagnóstico del cólico renal.” Radiología 57.2 (2015): 113-122.

- ÁLVAREZ, FA ORDÓÑEZ, et al. “Cólico nefrítico.” Bol Pediatr 48 (2008): 3-7.

- Freixedas, Feliciano Grases, A. Costa Bauzá, and Rafael M. Prieto. “¿Se puede realmente prevenir la litiasis renal? Nuevas tendencias y herramientas terapéuticas.” Archivos españoles de urología 70.1 (2017): 91-102.

This text is provided for informational purposes only and does not replace consultation with a professional. If in doubt, consult your specialist.